Book Tickets Online

About

The Tolpuddle Martyrs were a group of labourers from Dorset who were cruelly treated and made an example by landowners and the government when they formed a union and made representations about their pay and conditions. Their subsequent trial and penal transportation to Australia caused a public outcry and they were eventually pardoned and returned to England where a number of them were given farm land near Ongar before finally relocating to Canada.

Their Story

In Tolpuddle, Dorest in 1832, George Loveless, led a group of local labourers who were asking the farmers who employed them for a pay rise to ten shillings a week. The farmers agreed and then not only reneged on the deal, but reduced the wages to seven and then six shillings a week. George Loveless then sought help from The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union and formed a branch in Tolpuddle. To ensure secrecy, members were required to swear an oath.

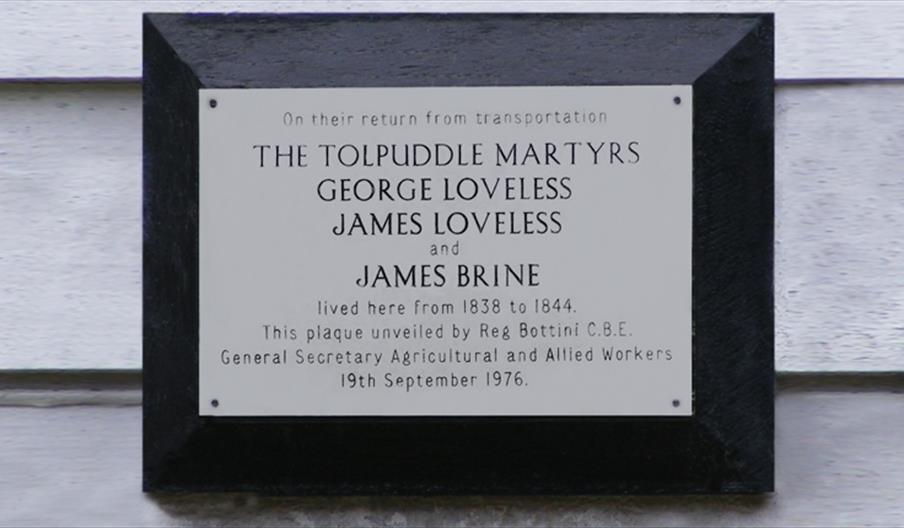

The local Squire turned to the Home Secretary who suggested that a law forbidding secret oaths, intended to prevent naval mutinies, could be used against the members of the union. With informants prepared to testify that oaths were taken, in 1834 George Loveless, James Loveless, James Brine, Thomas Standfield, John Standfield and James Hammett were arrested and taken to Dorset. There they were found guilty and sentenced to seven years penal transportation to Australia.

News of this turn of events quickly spread across the country and caused a public outcry supported by newspapers of every persuasion. The London Dorchester Committee was formed and mounted a campaign to win free pardons and 800,000 signatures were collected for their release. The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union orgainsed a march in London on Easter Monday and the government moved troops into the Capital. 35,000 people marched in silence to cheering crowds without any trouble.

Five of the six condemned men arrived in Sydney Australia in August with George Loveless kept in prison by illness and then transported to Tasmania arriving in September.

In March 1836 the new Home Secretary Lord John Russell granted pardons to all six on the proviso that each had a good conduct record. Delays in confirming their conduct, processing release paperwork and finding passage for them meant that they hadn’t all returned until August 1839. George Loveless was the first to arrive in England and he returned to Tolpuddle where he wrote ‘The Victims of Whiggery’ about his experiences.

To help them resettle, and with money raised by the London Dorchester Committee, farm leases were obtained near Ongar. Thomas Standfield and his son took over Fenner Farm at Tilegate Green, Higher Laver, whilst George and James Loveless and James Brine moved to Tudor Cottage at the larger New House Farm, Greensted. James Hammett lived at New House Farm for a few months after his return in 1839 but then returned to Tolpuddle to become a builder’s labourer. James Brine married Thomas’s daughter Elisabeth at Greensted Church. Although happy to marry the couple, the rector, Philip Ray, had nothing good to say about the Tolpuddle Martyrs moving into the area and preached sermons against them and complained to various local authorities about their presence and Chartist meetings attracting trouble to the area.

In December 1839 The Morning Post published a letter from an anonymous Conservative magistrate for the County of Essex, who wrote:

‘It is also true that these firebrands, the dreaded Dorchester Labourers, are four poor ignorant creatures, who literally do not even know how to plough the land they occupy. And…it is also true (and let me tell them they are marked men) That if these half dozen ignorant democrats (nether Essex men nor true agriculturalists are they) should attempt to disturb the peace of the county, they would be put down, not by the military force as at Newport, not by an armed gendarmerie of rural police but by the good sense and strong arm of the TRUE agricultural yeomen and labourers of Essex.’

Between 1844 and 1846 first the occupants of Tudor Cottage, and then Fenner Farm, emigrated from Essex to Canada. There is no direct evidence of what drove them to make this move but clearly little had changed in the attitudes of the gentry and land owners and, although they were now farmers rather than hired labourers, their beliefs were at odds with local feeling and seen to be a major threat. A move to a new world offered a new start and Canada was growing and attracting a great many people to relocate. They settled around London in Ontario where they became the backbone of the local Methodist community.