Book Tickets Online

About

David Livingstone

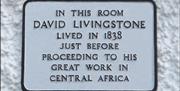

On Ongar High Street, just beyond the southern pinch-point and opposite the fire station, is blue plaque upon the wall of Livingstone Cottages. This marks the place where David Livingstone trained prior to his departure as a missionary to Africa. He lived in the room above the archway that leads to the United Reformed Church.

David Livingstone was a superhero of his day and stood for a range of Victorian values that exemplified a working class ‘rags to riches’ background which produced a scientist, explorer and missionary of extraordinary courage and determination. His adventures in uncharted Africa paralleled British colonial expansion whilst at the same time he was an advocate for reform and the ending of slavery and an obsession with discovering the source of the Nile.

His life started out with humble beginnings in Scotland. His father was a Sunday School Teacher with very strict religious views which he imparted to his son. David had a curious mind and, as well as religious tracts, his reading included books on science and in particular the natural sciences. His father saw conflict in his twin interests but the young Livingstone was able to reconcile science and religion and decided to leave his home town, where he worked in a cotton mill, and train to become a missionary. His aim was to answer an appeal for medical missionaries to go to China and he saved enough money to make his way into medical school. Whilst continuing his studies, Livingstone joined the London Missionary Society who sent him for further training at Ongar by the Rev. Richard Cecil.

At Ongar Livingstone joined other students to learn Greek, Latin, Hebrew and theology as part of their training to become ministers serving the London Missionary Society. The Rev Cecil said of Livingstone the scholar, that he was “worthy but not brilliant” and that his progress was “steady but not rapid.” He wasn’t very good steaking in front of people as demonstrated when preaching at a chapel in Stanford Rivers where he made such a poor job of it that he apologised to the congregation and left.

By the time Livingstone was ready to go abroad, China was out of the question as the First Opium War had broken out. Inspired by stories of the missionary work in South Africa and tales of uncharted lands, he turned his attention there and went to Botswana and then further into Africa to eventually become the first European to cross south-central Africa and declared the explorer who “opened-up” Africa.

In 1857 Livingstone resigned from the London Missionary Society to free him up to continue exploring and charting Africa to establish trade routes and thus displace the slave trade routes. He was also appointed Her Majesty’s Consul for Mozambique and areas west. To support his work he sent reports of his findings back to Britain and published books on his travels. From 1858 till 1864 Livingstone was funded by the British Government to explore and open up lands centred on the Zambezi River which was not very successful, the river being unnavigable dire to the number of cataracts and rapids that were impassable. In 1866 he returned to Africa and began his famous quest to find the source of the Nile. During this time he had various periods of illness, was deserted by his assistants and lost his supplies to thieves. He owed his life to Arab traders who he travelled with and became dependent upon. For six years he lost contact with the outside world until the American Henry Stanley found him on behalf of the New York Herald newspaper and uttered the famous words “Dr Livingstone I presume”.

Livingstone continued to explore Africa and died in 1873, aged 60, in Zambia. The cause of his death was a combination of malaria and dysentery. His heart was removed and buried where he died, a site now known as the Livingstone Memorial. His body was transported back to Britain and is buried in Westminster Abbey, as befitting for a Victorian hero.