Book Tickets Online

About

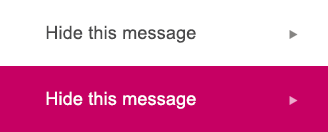

PLEASE NOTE. North Weald Redoubt is a scheduled monument, a rare survivor of the London Mobilisation Centres built to protect London from invasion, and of a unique design and construction. It is now privately owned and NOT OPEN to the public although it can be seen from paths around its perimeter. Unfortunately it has suffered from neglect and vandalism but the site is remarkably intact and unaltered. If you pass the site, remember that all the trees have been allowed to grow since it was abandoned - when it was built, it would have commanded views from its hill top vantage point all the way to Chelmsford and beyond.

What is the North Weald Redoubt?

The North Weald Redoubt, or to give it it’s technical title, The North Weald London Mobilisation Centre, is a Victorian fortification at the top of the hill behind the village hall. It sits within an area once known as Ongar Great Park, the oldest recorded park in England, originating in the Late Saxon period. built at the end of the nineteenth century, the Redoubt was one of the more substantial of a series of defensive positions, stretching 72 miles, built to protect London from invasion. The site reflects military design of the late Victorian era with casements in reinforced concrete and associated earthworks and defensive perimeter forming a low profile. The main building is D shaped with a curved front protected by sloping earthworks concealing tunnels leading from the centre of the site to forward trenches. Artillery stored on site would have been positioned on the roof to form a battery of six guns with ammunition fed by hoists from powder and shell magazines below. With the storage and transfer of explosives a dangerous activity, the magazines are laid out with specially designed corridors and fittings protected with half inch steel doors. The site was not designed to be permanently garrisoned but was maintained by caretakers living in the two single story slate-roofed cottages on the southern edge of the site alongside two wooden halls providing additional shell and cartridge stores. At times of war, the Redoubt would accommodate 72 men and was designed as a strongpoint which could hold out if the surrounding area was overrun, with defensive positions fronted by earthworks, trenches, special tall spiked Dacoit railings and wire fences around its full circumference.

Where was the threat from?

The nineteenth century saw rapid advances in military technology alongside a hostile stance from France, who had been investing heavily in enlarging and modernising her forces since defeat at Waterloo. The old Martello Towers built as coastal defence during the Napoleonic Wars were woefully outdated and experience during the Crimea War showed how formidable defences could protect ports and similar places of entry. French military activities and political posturing created a series of invasion panics in Britain culminating in The Defence Act of 1860 which gave the green light to the construction of fortifications to defend major ports starting with Portsmouth. However, the rapid development of iron-clad, steam powered ships, brought such advances in protection against defensive fire and manoeuvrability, that an invasion force was no longer deterred by shore forts or reliant upon capturing ports to land troops. This, coupled with a belief that the Royal Navy was no longer strong enough to defeat the rapidly growing French and Russian fleets, forced a major defensive rethink as Britain had not enlarged her army for home-defence believing that, as an island, her protection was the navy. Therefore, throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, accepting that an enemy landing and bridgehead might be successful anywhere along the coast, the decision was made to create a defensive stop-line inland. Drawn up in 1888, a scheme known as the ‘London Defence Positions’ called for regular troops to resist an invasion force at the coast for long enough to allow the construction of a continuous entrenched defensive line in the countryside around the Capital. Along the chosen line, buildings called London Defence Positions, were built to provide mustering stations containing stores for tools, materials and military equipment. Some, such as the redoubt at North Weald, were designed as more substantial fortifications able to mount guns.

Why at North Weald?

Where possible, the defence line utilised existing military sites, such as Tilbury Fort in Essex, but at various points new buildings were constructed with North Weald being one of the first, being started in 1889. North Weald was at the north-eastern end of a line that extended down to the Thames and along the Darenth Valley and southern edge of the Kent and Surrey Downs. The fortifications at the Redoubt face north, towards Chelmsford, designed to counter an enemy landing in the Wash and invasion routes down through Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridge.

If an invasion had happened, who would have garrisoned the Redoubt and how would they have been armed?

In 1881 the British army was reformed with regiments being named for the places in which they were based. As a result, the 44th (East Essex) Regiment and the 56th (West Essex) Regiment became the 1st and 2nd Battalions of The Essex Regiment with one serving abroad whilst the other stayed at home. Reforms had also shortened the length of time a man could enlist for, but also required those leaving the forces to go into the reserves for a number of years. In addition to the regular and reserve army, local defence was provided by part-time soldiers known as the militia. Some units of Essex militia had long histories and the threat of invasion throughout the nineteenth century saw the numbers swell. By the time of planning for the defensive line there were four volunteer battalions formed from the various Corps of Essex Rifle Volunteers, plus territorial artillery units, who would have been ready to deploy to defensive positions during an invasion.

As with naval warfare, coastal defence technology was moving apace throughout the Victorian era. During the Napoleonic Wars, Martello Towers mounted naval 24 pound, smooth bore, muzzle loading cannons using gunpowder to fire cannon balls, being guarded by soldiers armed with flintlock muskets. At the time of the 1860 Defence Act, fixed gun batteries had grown to 42 pound and smooth bore cannons were being superseded by rifled guns firing shells with more power, range and accuracy. In the hands of soldiers, flintlocks had given way to rifled percussion locks with regular troops soon to be issued with new centre-fire breech loading long arms. By 1904, when the Redoubt was completed, the army was armed with the Lee Enfield bolt-action magazine rifle, variants of which became the mainstay of the British and Commonwealth soldier right up to the 1950s. Volunteer territorial troops would have carried single shot Martini Henry rifles and carbines converted to chamber the same ammunition as the Lee Enfields. The guns mounted on the Redoubt would have provided by the Royal Field Artillery and would most likely have been the Ordnance Breech Loading 15 pounder which was being replaced in the regular artillery by the new Ordnance Quick Fire 18-pounder. The 15 pounder used a separate shell and charge and had a rate of fire of eight rounds a minute with a maximum range of 6,000 yards. These guns would have been stored at the fort and moved up onto the roof of the forward building when needed. Alternatively, mounting howitzers would have given indirect fire onto an enemy advancing across terrain past known fixed points allowing accurate range setting for every shot.

What happened to the site?

By 1904, when the construction of the Redoubt was completed, the Royal Navy was strong enough to stop any enemy at sea and the threat from France had diminished combining to make the defensive line redundant. However, the Redoubt remained a military base and was used as an arsenal during the First World War. In 1919 the site was bought by the Marconi Telegraph Company who built a radio station, with numerous masts on the hillside, using the Redoubt for storage (the concrete blocks used to anchor cables holding up the masts can still be seen amongst the grass on the hillside). Cable and Wireless took over the site and it was requisitioned by the military during World War Two when two machine gun turrets were added. In the 1950s the radio station was taken over by the General Post Office (GPO) who had rebranded as British Telecom by the time the site was decommissioned in the early 1990s.

Now a listed heritage site, the Redoubt is currently privately owned and fenced off, although unfortunately that hasn’t stopped extensive vandalism along with flood damage caused by poor stewardship. Even so, North Weald Redoubt is an important and significant military construction that has survived remarkably unchanged within its original setting whilst other Mobilisation Centres have been lost or substantially altered for alternative uses.

Our Redoubt remains an important and unique historical site providing a link to North Weald’s Victorian heritage and a strategic role in the defence of London which continued in the twentieth century with the establishment of vital air defences in both world wars and into the jet age.

People who enjoyed this page also enjoyed discovering the true story and hangman confession of Dick Turpin and Ongar – the Norman town and influence of the Counts of Boulogne

Information to accompany the pictures above

A. This illustration shows the fort that was finished in 1904 and is currently hidden under the trees. The main and defensible part of the redoubt is protected by a ditch and ‘unclimbable’ fence on three sides and the walls of the building across the rear which would have given the defenders facilities for direct and flanking rifle and machine gun fire. The D shaped building in the centre of the fort is protected by raised earthworks to the front that slope down to trenches for rifle and machinegun fire at their base. The trenches in turn are protected by larger sloping earthworks to the ditch. This design allows the fort to keep a low profile to attackers with the earthen banks ‘absorbing’ incoming shells or causing them to ricochet.

The D shaped building consists of a row of bomb-proof casements housing the shell and cartridge stores which feed the ammunition up to the guns mounted on the roof, firing over the raised earthwork. Hoists were used to lift the ammunition which would have consisted of separate charges or cartridges to propel the shells, and the shells themselves.

The larger casement to the rear, would have housed the artillery guns, small arms and ammunition, supplies for the fort, and the tools and stores required to construct the entrenched line towards the next centre at Brentwood. The site also had a large water supply.

All the buildings are connected by roadways and tunnels lead out to the forward trench positions.

Outside the defensible area are the two caretaker’s single story slate-roofed cottages and two large wooden halls added to increase storage capacity for ammunition and supplies. These buildings are constructed to standard military blueprints of the time and would have been replicated at the other mobilisation sites. Most have since been lost or altered beyond recognition making the ones at North Weald rare survivors.

B. This map shows the defensive line around London stretching from North Weald around to Guilford. Sections are named after the areas they pass through. Although shown as one line in this map, additional forward trenches, maybe as much as three deep, would have been constructed in some sections. Where possible, existing military establishments were utilised as part of the line. The land between the centres would have been surveyed by a team from the Ordnance Survey and plans drawn up to guide construction and ensure the trenches were built in the most advantageous and strategically important positions.

C. The North Weald Redoubt was designed using the latest ideas of the time reflecting the Seige of Plevna in 1877 during the Russo-Turkish war when Turkish forces, defending basic sloping earthwork, had repulsed numerous Russian assaults. The earthworks, created quickly and unobserved by the nearby Russian army, had absorbed Russian shells whilst the defenders, with modern repeating rifles and breech-loading artillery, had broken their attacks.

The idea of creating new and inexpensive forts, based on the Turkish experience, was taken up by military engineer Lieutenant-Colonel Sir George Sydenham Clarke. His sloping earthworks were put into reality by Sir Andrew Clarke, the Inspector-General of Fortifications, and resulted in a style of earthworks called the Twydall Profile. This was named after a village in Kent, near Chatham, where two experimental forts of this type were constructed at a total cost of only £6,000 compared with the £45,000 it would have taken to build a comparable stone forts to the previous standards . The design proved these quick and inexpensive constructions offered protection against shelling by the more powerful explosives being introduced.

The illustration shows the ‘profile’ or cross-section of the new design. To give some idea of the scale, the ditch was designed to be 15 or 20 feet (4.5 or 6 metres) below ground level. At the base of the ditch, an unclimbable fence, recommended to be 9 feet 6 inches (2.9 metres) tall, was placed. These were often referred to as a "Dacoit fence", and a photograph of a surviving fence is show in the picture. The 10% angle of the slope between the ditch and rampart was found to be the best at promoting shells to ricochet and the slope itself would have had barbed wire added to further hinder attackers.

D. This photograph shows the French Ironclad Redoutable, the world’s first all-steel constructed warship. Although primarily steam powered, it still retained masts and sails marking its transition from sail to steam. It was the rapid development of such warships that shattered the Royal Navy’s supremacy at sea and ended the belief that any invading force would be defeated at sea before it even made landfall. Both France and Russia were level with Britain in the technology race to produce bigger, faster and more powerful fleets.

A contemporary description of Redoutable in an American magazine said:

"The Redoubtable is built partly of iron and partly of steel and is similar in many respects to the ironclads Devastation and Courbet of the same fleet, although rather smaller. She is completely belted with 14 inch [360 mm] armour, with a 15 inch [380 mm] backing, and has the central battery armoured with plates of 9½ inch [240 mm] in thickness.

The engines are two in number, horizontal, and of the compound two cylinder type, developing a horsepower of 6,071, which on the trial trip gave a speed of 14.66 knots. Five hundred and ten tons of coal are carried in the bunkers, which at a speed of 10 knots should enable the ship to make a voyage of 2,800 nautical miles [5,200 km]. Torpedo defence netting is fitted, and there are three masts with military tops carrying Hotchkiss machine guns.

The offensive power of the ship consists of seven breechloading rifled guns of 27 centimetres (10.63 inch), and weighing 24 tons each, six breechloading rifled guns of 14 centimetres (5.51 inch), and quick-firing and machine guns of the Hotchkiss systems. There are in addition four torpedo discharge tubes, two on each side of the ship.

The positions of the guns are as follows: Four of 27 centimetres in the central battery, two on each broadside; three 27 centimetre guns on the upper deck in barbettes, one on each side amidships, and one aft. The 14 centimetre guns are in various positions on the broadsides, and the machine guns are fitted on deck, on the bridges, and in the military tops, four of them also being mounted on what is rather a novelty in naval construction, a gallery running round the outside of the funnel, which was fitted when the ship was under repairs some months ago.

There are three electric light projectors, one forward on the upper deck, one on the bridge just forward of the funnel, and one in the mizzen top"

Redoutable came into service at the end of 1878 and served until 1911 when she was demolished in Saigon.

E. This photograph shows an artillery crew firing the British 15 pound breech-loading gun of 3 inch calibre weighing 7cwt. These guns used shrapnel shells extensively and the insert shows details of a shell.

The description breech-loading refers to the ability to open and close the barrel at the rear, to insert the ammunition. Advances in design and engineering, had enabled strong and effective sealing of the breech when closed. Until the second half of the nineteenth century, the inability to achieve a reliable gas-tight seal at the breech meant that barrels had only been open at the muzzle necessitating loading of the explosive charge and projectile all the way down the barrel. This meant the crew were exposed to fire, in front of the gun, when loading and needed loose fitting projectiles to enable them to be pushed down to the breech when the gun was hot and fouled. Muzzle loading was also time consuming. The new breech loaders could use tighter-fitting ammunition, be fired at a much faster rate and the crews could remain behind the ramparts or protected by shields as they worked.

Shrapnel shells were used against troops in the open and consisted of a shell casing containing a central exploding charge surrounded by small balls (41 per pound) which would fly out when the shell detonated. Fuses could be set to explode on impact or in the air. Shells containing explosive only were designed for use against buildings and ships, so of limited use in forts facing attackers over open ground.

F. As an alternative to field guns, the forts could have mounted howitzers. These guns were designed to fire at a high angle of elevation, typically 45 degrees. This allowed for curved or indirect fire, ideal where the attackers were dug in or sheltered behind obstacles. As with the field guns, howitzers fired shrapnel and at lower and more direct elevations, case shot. Case shot was a canister containing many small balls, but no exploding charge, making it like an enlarged shotgun cartridge.

The top photograph shows the breech hinged open and a shell inserted on the howitzer in the foreground. The lower photograph shows the barrels at maximum elevation. The insert shows case shot.

G. The period during which the North Weald Redoubt saw active service was a time of great change in the world of small arms (those carried by soldiers). In rapid succession, the latter part of the nineteenth century had seen the development of self-primed metallic cartridges and breech loading, and then the introduction of ammunition magazines for rapid firing, culminating in the hand-cranked and then fully automatic belt-fed machine gun. This period also saw the end of gunpowder as new developments in chemistry created mixtures that produced far more powerful propellants. These had the added advantage of not creating the clouds of white smoke that gunpowder had produced, giving away the shooters position and covering the battlefields. In line with these changes, new smaller ammunition was required, and the British introduced a cartridge of .303 calibre that was to remain in service (albeit with propellant upgrades) until the 1950s.

By 1904, when the redoubt was completed, the British soldier carried the Lee Enfield rifle (1) which had a magazine capacity of ten rounds and a range further than the eye could see. It was issued with the Pattern 1888 bayonet shown sheaved (2) and unsheaved (3).

In order to provide enough weapons to utilise the new smokeless ammunition in the new calibre, servicable Martini-Henry rifles were taken from store and re-barrelled. These Martini-Enfields were issued to reserve troops and local militias (although some militias had the funds to purchase their own weapons and therefore often had the most up to date arms). The Enfield-Martini shown in the photograph (4) was converted in 1897 from a Martini-Henry rifle to become an artillery carbine and its brass butt-disc (5) indicates that it was last issued in December 1909 to the 1st Wessex Brigade (1. WX.) of the Royal Field Artillery (RFA), at that time a reserve unit. The Martini-Enfields used the same bayonet as the Lee Enfields.

The Martini system fired the .303 cartridge (6) individually whilst the Lee magazine system held ten rounds in the magazine which was loaded from five-round ‘chargers’ (8) carried in belt pouches.

The photograph shows older reservists during the First World War, typical of the troops who would have guarded North Weald Redoubt (and fore-runners to the Home Guard in the Second World War). They are all armed with Martini Enfield artillery carbines.

H. This photograph shows a typical group of artillerymen around 1900, posing alongside a stack of shells.

I. This illustration shows the kind of basic trench that might have been constructed in haste forward of the main entrenchment line, here under attack. The soldiers are armed with Lee Enfield magazine rifles and a Maxim machine gun. The man carrying the ammunition box is a reminder of the massive increase in ammunition required by the new machine guns and rapid-fire bolt-action magazine rifles.

If the Russo-Turkish War had taught the British Army valuable lessons in modern fort construction, the very recent Second Boer War in South Africa (1899 - 1902) had been a lesson in the new tactics required by the introduction of modern firearms with increased firepower, range and accuracy. This illustration is actually of a Boer attack on a British trench in South Africa, but it could equally have been a French attack on a trench between Brentwood and North Weald!